Dreweatts Collecting Guides | Bronzes of the Long 19th Century

A striking bronze can add a vivid and three-dimensional element to your interior and your art collection. The 19th century was punctuated with stylistic revisits and revivals, and offers a rich variety of subjects to suit every collector, from Grand Tour models after the Antique to romantic maidens and busts.

Dreweatts' Sculpture and Works of Art specialist, Charlotte Schelling, looks at our Fine Furniture, Sculpture, Carpets and Ceramics auction on Tuesday 19 May, and shares her top tips on what to look out for when collecting 19th and early 20th century bronzes.

What's in a name?

One feature which makes later 19th and early 20th century bronzes such a rich and interesting area to collect is that they are often signed, at least more so than their predecessors. This allows specialists and buyers alike to find out a great deal about a work of art on initial inspection.

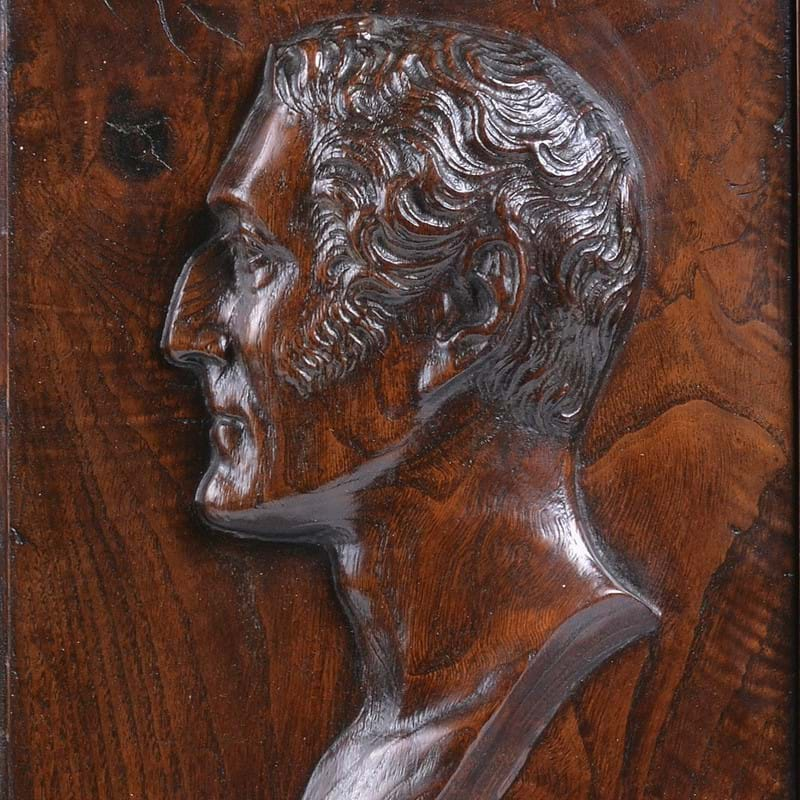

For example, Lot 253 in the sale is variously inscribed, and shows the name of the sculptor (P. Vaudrey), the name of the subject (Robert Bain) and even the date the model was exhibited at the Salon (1905). In this case, Pierre Vaudrey’s proud claim of authorship allowed us to figure out the back story to this fascinating work: Vaudrey was primarily a funerary sculptor, and this model corresponds to a larger grave monument for the son of a wealthy bourgeois inventor, which is at the famous Parisian cemetery of Père Lachaise.

Signatures often take the shape of inscriptions to the maquette or model so the name is incorporated each time the bronze is cast. They can often be found on the (integral) base or rear, in the case of busts they may appear along the truncation.

Eye for detail

Scientific and technological innovations during the century changed bronze manufacture significantly. The early 19th century was still characterised by many of the hand-finishing processes which were an integral part of 18th century bronze production. Note for example the hair of the Empire bronzes of winged youths in Lot 150, which shows signs of delicate chasing (chiselling by hand after casting) to each individual curl.

With the advent of the industrial revolution in the second half of the century and stretching into the 20th century, bronzes came to be produced in larger quantities, and though many fine and excellent bronzes were made and chasing by no means went out of fashion in good workshops (see for example the group of Venus and Cupid by Belgian sculptor Charles-Auguste Fraikin), the quality can be more varied.

Specialist's Top Tip: Zone in on the finer details such as the fingers, toes and faces, and see how crisp and well-defined they are. Loss of defined contours can indicate a later or poorer cast.

Hands-on approach

Another way in which you can gauge the quality of a piece is to really get stuck in. As mentioned above, the 19th century is a time of extensive scientific innovation. One such innovation is the medium of spelter: a zinc alloy which can be (convincingly) cast and patinated to simulate the more costly material of bronze, though it is a lot tinnier to the touch. Prospective buyers of bronzes (of all ages) should not be afraid to get a bit handsy with works: tap the surfaces, trace the lines of the faces and draperies to feel how fine they are. A good bronze will have a nice weight to it and a resonant and warm ring when tapped.

Foundry facts

Do keep an eye out for foundry marks or stamps (sometimes shaped like a little medallion, or otherwise an inscription), as these can add another layer of interest to the work. Not only are some foundries synonymous with quality finish (such as that of Ferdinand Barbedienne in Paris, or the workshops of the Righetti and Zoffoli families in Italy), but a foundry mark can also place your bronze at the right place and the right time.

Lot 271, the characterful bust of Diana the Huntress by Falguière, bears the mark of the Thiébaut Frères. The sculptor himself is known to have enlisted this foundry to cast the model in the 1880s, which places this cast in closer proximity to the artist.

On the surface

The question of surface is less straightforward: patination (the layer of texture and colour which is created by applying chemicals to a bronze after casting) is really a matter of personal preference, and in fact clients would often be able to pick a colour and finish when commissioning or acquiring works from foundries or retailers. Furthermore, while smooth and glossy finishes can be the hallmark of a fine bronze, in some cases textured surfaces are an integral part of the design.

Lot 267 for instance, a bronze of Pandora, which we have attributed to English sculptor Harry Bates ARA, has a much more loosely modelled surface. The bronze is possibly a maquette for Bates’ circa 1890 larger marble group of this subject in the Tate collection, and the lively, gestural modelling is in line with the work’s nature as a sketch.

AUCTION DATE & LOCATION

Tuesday 19 May | 10.30am

Dreweatts, Donnington Priory, Newbury, Berkshire RG14 2JE

This is an online auction with an auctioneer.

VIEWING:

- Our specialists will be providing detailed conditions reports and additional images as requested.

- Our Remote Viewing Service also allows you to preview the auction from the comfort of your own home at a time convenient to you | Find out more

- If government regulations permit, viewing at Donnington Priory will be offered on a by appointment basis from Monday 11 May.

View online catalogue

View page turning catalogue

CONSIGN TO A FUTURE AUCTION

To consign to a future auction or to arrange a free auction valuation, please contact Charlotte Schelling at: sculpture@dreweatts.com

Or complete our free online valuation form here.