The Collection of Pablo Bronstein by Michael Diaz-Griffith

To start our 2024 auction calendar, we are pleased to present our auction Pablo Bronstein: Diversions of a Contemporary Mind on Tuesday 9 January. The auction offers Old Master pictures, rare English and Dutch delftware, fine and decorative furniture, as well as silver from the private collection of Argentinian contemporary artist Pablo Bronstein. Here, author Michael Diaz-Griffith, tells us more about Pablo's collection.

The Collection of Pablo Bronstein by Michael Diaz-Griffith

Twelve months ago I wrote an essay, excerpted below, about one of Britain’s most intriguing collectors: Pablo Bronstein. At that time, it would have been impossible to imagine the dispersal of Pablo’s collection, which he assembled with the eye of an artist (as that is what he is) and the seriousness of a connoisseur (because he is one of these also). Indeed, whenever I am asked to name a “grown-up” collector below the age of 50 or so, I mention Pablo, whose practice giddily spans disciplines, but never at the expense of rigor – a quality that combines alchemically with devilish creativity in everything the globally renowned artist does.

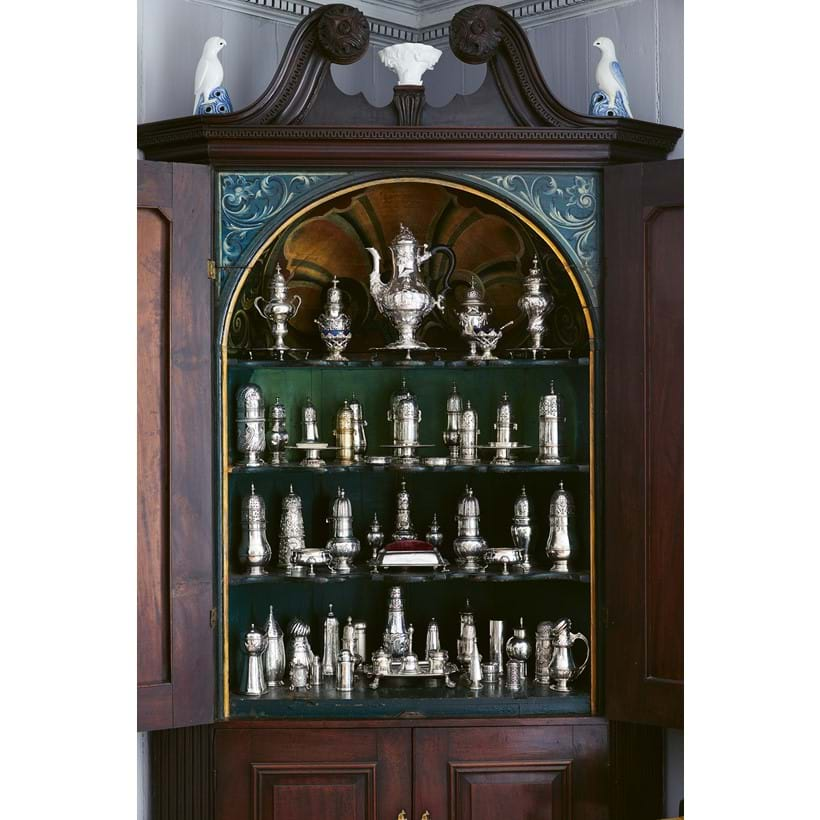

One glance at his collection of eighteenth-century silver sugar casters, quite possibly the finest in private hands, and you will see what I mean. It is an ingenious grouping, and if you are familiar with Pablo’s work, you may recognize some of the forms from his drawings, which recast the objects as ruinous monuments or marooned spacecraft: fussily ornamental but also baldly phallic and strangely elemental. At the same time, each one of the casters - or the whole set - could happily live in a national museum. I suspect that the connoisseur in Pablo would have placed them there.

The artist, however, wins out. Just as Pablo completes one series and moves on to another, he has decided that his collection, in its present form, is complete. As an index of aesthetic and historical obsessions; a collecting performance; and an installation, at his cottage in Deal, you might say it has achieved its final state. It follows, for an artist like Pablo, that such a collection is ready to be spread to the four winds.

Happily for us, that means our own collections, where each object pictured here, no matter its age, will be reborn into a new life. This cycle of rebirth is the soul of collecting, and looking back, I should have expected that Pablo would hasten the cycle. He always is one step ahead.

Lucky are we who follow in the artist’s footsteps.

The New Antiquarians: At Home with Young Collectors

The aesthetic lives of young gay men are easily misunderstood. In the case of Pablo Bronstein, the Argentine-British artist, it has become apocryphal that his grandmother gave him a silver sugar caster at age sixteen, thereby sparking a formative obsession, a lifelong collecting practice, and perhaps even Pablo’s career. As a neat little dream of generational inheritance, it’s an apocryphon that is difficult to resist.

Of course, almost the reverse is true: after he developed the first stirrings of intensity for the antique silver caster, Pablo convinced his grandmother to yield it to him. Like a magnet, he had drawn the silver caster toward himself—the first of many objects that would pass into his possession, and perhaps his soul, through his own efforts. He had become a collector.

If silver sugar casters didn’t exist, Pablo would have invented them. Like so many boys of his disposition, he had a habit of drawing grade-school capriccios: imagined architecture, invariably in the grand manner, that would have been buildable in a more interesting age. In the same year he took possession of the caster, Pablo redecorated his bedroom in “crappy” (his word) Neasden, a northwest London suburb.

I have not seen photos of the room, but it is said to have resembled a Baroque palazzo. Perhaps his grandmother’s elegant home in Buenos Aires was an inspiration. I suspect that most of the decor was derived from interior decoration magazines and the young Pablo’s fevered imagination.

Like so many boys of his disposition, Pablo proceeded to architecture school, but that is also where his story began to diverge. In a more interesting age, architecture school would have suited him better, and our world would brim with Rococo skyscrapers, brutalist grottos, postmodern follies, and Baroque parking garages designed, with disarming seriousness, by Pablo Bronstein. Pablo is no fool, however, and he quickly understood that his capricious inventions could only be realized, in the real world, as contemporary art. Since then, his work has become even more gloriously unbuildable. The boy from Neasden builds castles in the sky.

Closer to earth, in the sleepy seaside-holiday town of Deal, he builds a collection — and a total environment to contain it. The place was not much to begin with (“an exciting modern Shaker-effect kitchen with pewter-feel handles,” read the real estate ad), but that was before it became an unrestrained manifestation of everything an artistic practice cannot be, that a house and collection can. Now it is undoubtedly too much, which is just right.

The hectic “Chinese” room that mercifully replaced that “Shaker-effect kitchen,” for instance, looks like nothing more than a ship’s cabin designed by Thomas Chippendale—if he were drunk on Chartreuse. There’s nothing Chinese about it, and that’s the point. The boy from Neasden loves things that are not what they are. If that sounds “camp” to you, Susan, it is only to the extent that material culture has always embodied those qualities we narrowly associate, today, with Sontag’s famous concept: “artlessly mannered or stylized,” “self-consciously artificial and extravagant,” “teasingly ingenious and sentimental,” to quote the dictionary definition. And indeed, the room’s topsy-turvy take on chinoiserie evokes History more fully than any norm-following period room ever could.

It follows that a museum-quality collection of casters figures prominently in the scene. Not that any museum will possess such a collection until Pablo bequeaths his; the grouping, like Pablo’s collecting practice, is sui generis. When he began collecting casters serially, he says, he would buy on impulse, struck by the same feelings of intensity that started him down the path to connoisseurship. Squint at a caster long enough and you may begin to see an ornament-encrusted phallus topped by a rather suggestive dome. That is what Pablo sees. When a caster looks just right, it is, in a familiar way, irresistible.

But resist Pablo must, as all of us with expanding collections and shrinking storage must resist, and in recent years he has become scrupulously selective. Will a new acquisition fill a hole in his collection? Will it be as good as or better than the current best example? One day I ask him about this, but my notes are mostly obscured. Instead I see, written out in a clear hand, “Paul de Lamerie—silver centerpiece—spidery, spindly—ultimate acquisition.” In other words, the crown jewels for collectors of eighteenth-century silver—not just Rococo, but among the most Rococo things ever made.

If de Lamerie centerpieces didn’t exist, I fancy, Pablo would have invented them.

This essay is excerpted from The New Antiquarians: At Home with Young Collectors (2023) by Michael Diaz-Griffith, with permission from Phaidon/The Monacelli Press. All photos by Leon Foggitt.

View page turning catalogue

Auction Details

Tuesday 9 January 2024, 10.30am GMT

Donnington Priory, Newbury, Berkshire RG14 2JE

Browse the auction

Sign up to email alerts

VIEWING:

- Viewing in Newbury:

- Friday 5 January: 10am-4pm

- Sunday 7 January: 10am-3pm

- Monday 8 January: 12 noon-4pm

- Tuesday 9 January: from 8.30am

- Remote Viewing | Learn more