Sneak Peek | Fine Clocks, Barometers and Scientific Instruments | 27 February

We continue to welcome entries for our forthcoming auction of Fine Clocks, Barometers and Scientific Instruments until 9 January 2024. Ahead of the auction, which takes place on Tuesday 27 February, Head of Department, Leighton Gillibrand provides a sneak peek at a fine William and Mary ebony table clock which will be offered in the auction.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of my role as a clock specialist is that you never stop learning with the best tutors being the clocks themselves. When considering clocks made during the ‘golden age of English clockmaking’ (circa 1630-1700) God really is the detail, and it is only through close examination that secrets are often revealed.

One of the entries for our forthcoming Fine Clocks, Barometers and Scientific Instruments sale does indeed have something to tell us, and this relates to who made what for whom! The clock in question is not strictly a clock but a timepiece insomuch that it does not strike the hours through normal operation. Technically speaking a ‘clock’ should incorporate a striking mechanism with the origins of the word itself referring to the bell of a timepiece (think ‘cloche’ in French or ‘glocke’ in German) rather than the timekeeping aspect of the mechanism. Although this timepiece does not automatically announce its presence on the hour it does, however, incorporate a mechanism which sounds the hour and last half hour on demand only - by pulling on a cord that exits the case. This unusual system is termed ‘silent pull quarter-repeat’ which, to horologists, indicates that the clock is indeed silent unless asked. Timepieces of this specification were made with the bedchamber in mind, allowing the owner to ascertain the time in the dark without having to take the trouble light-up a candle. At the time this timepiece was made (circa 1690) clocks were very expensive luxury items that could only be afforded by the wealthiest of individuals. In most cases even very affluent households could afford to possibly have two or three clocks; a longcase ‘house’ clock for the entrance hall; a weight-driven short duration alarm timepiece (a lantern or hook-and-spike clock) to wake the servants; and a spring clock for the drawing room which would also be taken upstairs to the bedchamber at night. With this in mind, for an owner to afford a timepiece for exclusive use in the bedchamber, then they must have been a particularly wealthy individual.

So, we know that the timepiece in question dates to around 1690 and is a ‘silent pull quarter-repeating spring table clock', now let’s look at who made it. The backplate is signed ‘Samuel Watson’ but with no place name (such as ‘London’) given – a very unusual omission on a clock of this date. What do we know about Samuel Watson? Well, quite a lot actually as he was an fairly important character in horological, mathematic and scientific circles during the 1680’s and 90’s. Originating from Coventry and working there from around 1680, Watson clearly demonstrated a remarkable aptitude for the application of mathematics to horology, even grabbing the attention of the Royal Court with commissions for a complex astronomical clock for Charles’ II bedchamber in 1682; followed by another ‘The Celestial Orbitary’ in 1683. The first of these two timepieces was the first complex astronomical clock to be made in England since the great late Medieval Cathedral clocks such as Wells and Exeter. The second took six-years to complete, by which time Charles II had been succeeded by James II and then William and Mary. Funding for the ‘The Celestial Orbitary’ proved a challenge for Watson, however Queen Mary eventually agreed a settlement together with a ‘service contract’ with the clock taking residence at Hampton Court. Watson made at least two more astronomical clocks, one of which resides in the Clockmakers’ Museum collection and is thought to have been made for Sir Isaac Newton.

In addition to the mathematics of astronomy and how this could be applied to horology, Samuel Watson, through his connection with John Floyer – a physician based at nearly Lichfield, made the earliest known timepieces specifically developed for a medical application. Dr. Floyer was the first to suggest that the timing of the pulse could provide valuable diagnostic information and, working with Watson, announced the creation of the ‘pulse watch’ (essentially a form of early stopwatch) in 1707. Curiously, during the mid-1690’s Samuel Watson produced a series of further small ‘silent pull quarter-repeating’ table timepieces (not dissimilar to the present clock) that also incorporated centre-sweep seconds with the hand completing a revolution every two minutes. Recent investigations collated and described by Sunny Dzik in his excellent publication BENEATH THE DIAL, English Clock Pull Repeat Striking 1675-1725 (pages 99-100), provide detailed analysis of how this complex feature was incorporated into the movement. In light of Watson’s association with Dr. Floyer, it is tantalising to theorise that the inclusion of this additional feature was to create a timepiece primarily with physicians in mind.

No doubt to be closer to his peers, both in academia and horology, Samuel Watson moved to London where he was admitted as a ‘Free Brother’ of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1692. His admission as a Free Brother indicates that he was awarded this privilege on his own merits rather than having to serve an apprenticeship. When considering the signature on the present timepiece, the lack of place name would suggest that it was made prior to his move to London in 1691. If this were the case, then why is Coventry not included alongside his signature? This answer may well lie in the fact that the timepiece was made in London, but not by Samuel Watson.

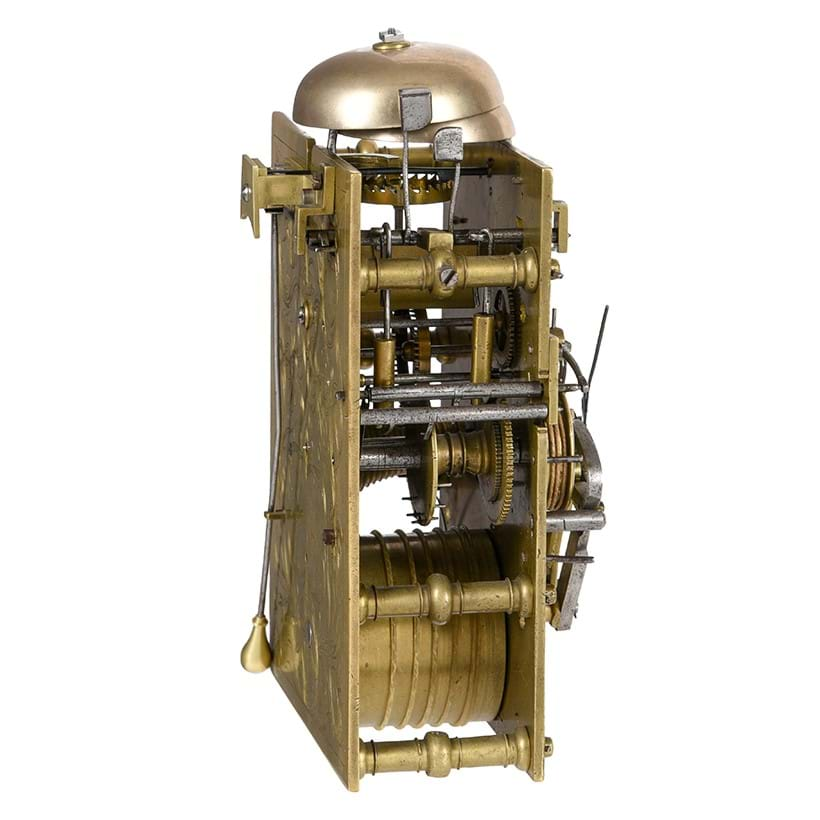

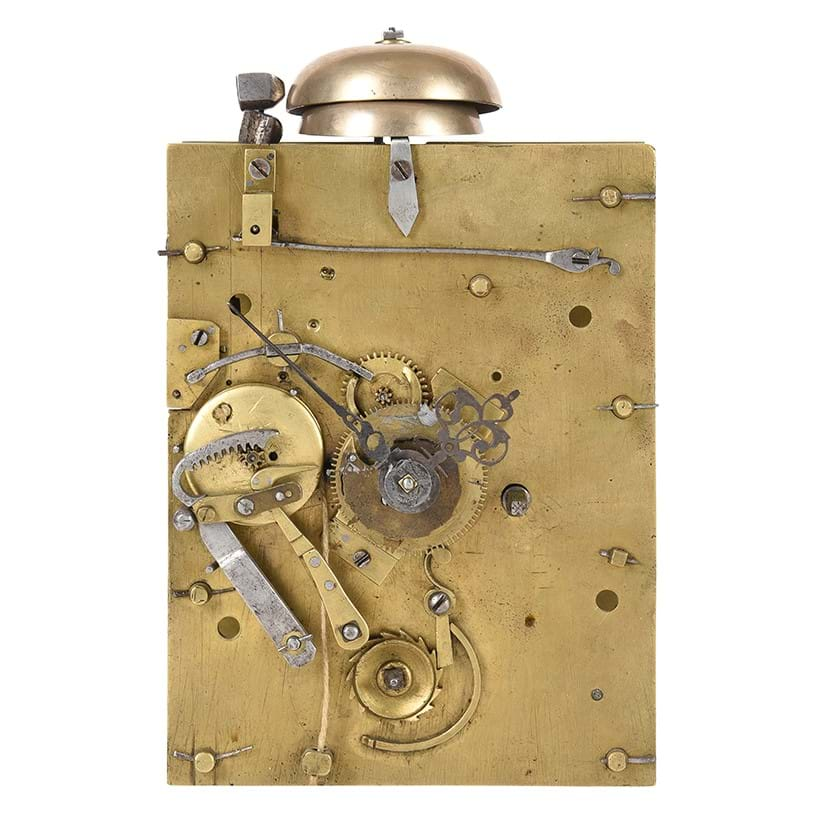

As Head of Clock for Dreweatts with the best part of 25 years of auction experience I have been blessed with the opportunity to handle examples from all the leading London workshops operating during the ‘Golden Age’ of English clockmaking. With this comes the ability to recognise details and traits specific to certain makers. Confronted with the present timepiece I spotted a few somewhat idiosyncratic details which seemed familiar, hence warranted further investigation. Perhaps the most obvious of these (to a horologist!) was the unusual positioning of a hammer blade-spring across the top of the finely engraved backplate. This is a rare feature as most makers place such springs between the plates to keep the engraved decoration as uncluttered as possible. This detail ‘rang a bell’(!) with me and a quick bit of delving into our past sale records and the right publications revealed the true identity of the present timepiece. Fortunately, my first port of call - Sunny Dzik’s tome on English clock repeating work, immediately confirmed my suspicions. In section 1 of BENEATH THE DIAL, English Clock Pull Repeat Striking 1675-1725, Sunny Dzik describes three clocks by the eminent London clockmaker Henry Jones (pages 67-72). Placed in chronological order, the second of timepiece in this group is as near identical to the present timepiece as can be expected in a 330-year-old hand-built timepiece. In addition to having the horizontal hammer leaf spring across the top of the backplate, both clocks share essentially identical layout to the repeat-striking mechanism and have backplates engraved by the same hand. In addition to this, both dials share the same design of half-hour marker to the chapter ring and have matching details within the case - such as the upper and lower mouldings and layout of the side apertures.

Further wider investigation into our past sale records revealed that Dreweatts sold another very similar timepiece by Henry Jones in March 2015 which further serves to confirm the true origins of the example in question. Henry Jones was an important maker most notably for continuing the highly distinctive approach of his former eminent Master, Edward East. Both Henry Jones and Edward East were Catholics with the latter serving as clockmaker to Charles II. The attribution of the present timepiece to the workshop of Henry Jones would indicate that Samuel Watson had a working arrangement with him and, as such, probably knew Edward East. This possibility is further reinforced by Watson’s Royal commissions.

At the time Samuel Watson was setting up in London, Henry Jones’s career was nearing its end. He served as Master of the Clockmaker’s Company in 1692 but stopped attending in 1694 and died the following year. The present timepiece therefore must have been supplied to Watson before 1694. Indeed, when considering the working dates/locations of both makers, it would perhaps be appropriate to suggest that it was most probably supplied during the time Samuel Watson was relocating from Coventry to London, hence prior to him becoming a Free Brother of the Clockmaker’s Company in 1692. Prior to this date he would not be permitted to sign a clock as London made.

When considering Samuel Watson’s work as a whole it is clear that he subsequently produced a higher proportion of this type of ‘silent pull quarter-repeat’ timepiece than his peers. As previously speculated the incorporation of centre seconds within the specification of these later examples may indicate that they were intended for use by physicians. However, when comparing these later examples with the present timepiece, strong similarities in the design and layout of their mechanisms can be seen. This suggests this example (made in the workshop of Henry Jones) probably served as a sort of prototype for his later examples. The relatively high proportion of this relatively rare variant of timepiece, traditionally designed for use exclusively in the bed chamber, may be connected to the fact that Samuel Watson made a clock for Charles II’s bed chamber early in his career. This Royal commission could have created a demand for ‘bed chamber’ timepieces from the very maker who supplied the King.

This journey down a horological rabbit hole illustrates how a timepiece can ‘talk to us’ in order to reveal its secrets. These secrets add to knowledge, in this case we now know that Samuel Watson had some form of working relationship with Henry Jones, something which has not been noted before. The William and Mary silent pull-repeating ebony table timepiece by Samuel Watson will be offered in our forthcoming Fine Clocks, Barometers and Scientific Instruments auction which takes places on Tuesday 27 February 2024.

Auction Details

We continue to welcome consignments for the next curated sale of Fine Clocks, Barometers and Scientific Instruments scheduled for Tuesday 27 February 2024.

Thinking of selling or wish to discuss a possible consignment? Please contact our specialists for further information and guidance. Entries close on Tuesday 9 January.

Leighton Gillibrand | clocks@dreweatts.com